Barcelona’s ‘Superblocks’

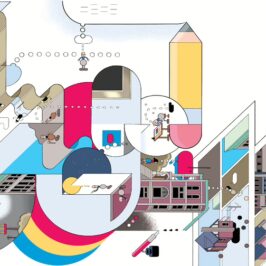

Imagine if streets were for strolling, intersections were for playing and cars were almost never allowed.

While it sounds like a pedestrian’s daydream, and a driver’s nightmare, it is becoming a reality here in Spain’s second-largest city, a densely packed metropolis of 1.6 million on the Mediterranean. Ever since the 1992 Summer Olympics focused global attention here, this thriving center of tourism, culture and business — often viewed as a hipper, more easygoing cousin to Madrid, the Spanish capital — has seen its popularity soar along with congestion on its streets and sidewalks.

So in an initiative that has drawn international attention and represents a transformative remaking of its streetscape, Barcelona has decided that many of its car-clogged streets and intersections will hardly have cars at all. Instead, they will be turned over to pedestrians.

Beginning in September, city officials started creating a system of so-called superblocks across the city that will severely limit vehicles as a way to reduce traffic and air pollution, use public space more efficiently and essentially make neighborhoods more pleasant.

“We like to call it ‘winning back the streets for the people,’” said Janet Sanz Cid, a deputy mayor of the city. “People from Barcelona want to use the streets, but right now they can’t because they are occupied by cars.”

Under the plan, the superblocks will be overlaid on the existing street grid, each one consisting of as many as nine contiguous blocks. Within each superblock, streets and intersections will be largely closed to traffic and used as community spaces such as plazas, playgrounds and gardens. Ms. Sanz said that at least five superblocks were expected to be designated by 2018.

Barcelona’s system of superblocks — called “superilles” in Catalan — would go well beyond the pedestrian plazas that have sprouted up on the streets of New York City. While those spaces have carved out more room for pedestrians in busy corridors, the superblocks represent a more radical approach that fundamentally challenges the notion that streets even belong to cars.

The strategy has propelled Barcelona, a city better known for its soccer team and its Gaudí architecture, to the forefront of urban-transportation experiments and has attracted interest from transportation officials, urban planners and advocates in many other cities paralyzed by gridlock.

Claire Weisz, an urban designer at WXY, a Manhattan firm that redesigned the streets around Astor Place, said Barcelona’s superblock plan could be applied in New York to redefine streets as public spaces. “The vast majority of people living in our neighborhoods don’t have cars,” Ms. Weisz said. “Yet our streets are primarily used by cars, and we have a huge need for safe places to walk and bike.”

Barcelona’s plan will redirect cars, buses and commercial vehicles to streets along the perimeter of each superblock, though local residents will still be able to drive their cars at reduced speeds and park in designated areas. Deliveries will be allowed at less congested times.

But as Barcelona officials have acknowledged, introducing the superblocks will not be as easy as simply changing the rules. To be widely accepted, the plan will require a cultural shift in the way people view and use the streets.

The first of the new superblocks received a mixed reaction when it was unveiled recently in El Poblenou, a former industrial area that has been redeveloped with low-income housing and offices for technology companies. Though many residents saw the benefits of the superblock, some complained that they were not given enough time or explanation before it was put in place. Businesses have also expressed concerns that it could interfere with their work by, among other things, restricting when they can load and unload goods.

To inaugurate the superblock, architecture professors and students have worked with local associations of residents and businesses to come up with alternative uses for the street space. One intersection, using tires and recycled materials, was transformed into a playground with a soccer field and sandbox.

Marta Louro, 40, a teacher who lives next to an intersection, said the superblock would make streets safer and reduce pollution. “It gives priority to the pedestrian,” she said. “I believe it’s very important that people have space.”

But others have expressed concerns that they will have to walk farther to a bus stop, or will have a harder time using their cars or finding parking. “It’s not a bad idea,” said Oriol Sanchez, 25, a waiter who drives to work. “But for me, it’s a problem for my car.”

Visitación Soria, 78, said the superblock would not be embraced by everyone. “People like their cars,” she said. “People are already saying there’s a problem finding parking, and this will make it worse.”

No matter the merits, the debate over what a modern urban streetscape should look like, how it should function and whom it should serve has grown increasingly clamorous around the world. In New York City, whose population is at a record high of 8.5 million residents, conflicts among pedestrians, cyclists and motorists have drawn attention to busy corridors. Transportation officials have recently takensteps to expand the overtaxed promenade on the Brooklyn Bridge.

Polly Trottenberg, the city’s transportation commissioner, said that 53 pedestrian plazas had been built, in Times Square and other parts of the city, since 2007, and that another 20 plazas were under construction. In all, these plazas will total 27 acres, roughly the equivalent of 20 football fields, Ms. Trottenberg said. “It’s not an insignificant amount of space that we’ve wrestled back from the automobile,” she said.

Ms. Trottenberg said she was aware of Barcelona’s superblocks plan and would consider applying the concept in New York — if not the name. In urban planning circles, the term “superblock” has been used to refer to sprawling public housing projects in American cities. “We’re certainly formalizing things that are close to that concept,” she said. “There are a lot of different models, and there’s not a one-size-fits-all.”

The city tried a one-day “Shared Streets” test in August that promoted recreational use of a 60-block area of Lower Manhattan. The speed limit was reduced to 5 miles per hour, and people were encouraged to take to the streets alongside cars. The program was intended to expand on another initiative, “Summer Streets,” in which a section of Park Avenue south of 72nd Street and all of Lafayette Street were closed to vehicles on three August Saturdays.

Leave a Reply