La Ricarda or Casa Gomis, completed in 1963, is one of the key midcentury buildings in Spain. Located by the Mediterranean Sea in El Prat de Llobregat, a town 10 miles southwest of Barcelona, the house was commissioned by Ricardo Gomis and Inés Bertrand in 1949. Barcelona-born architect Antonio Bonet Castellana, who had trained with Le Corbusier and Josep Lluís Sert, designed the house while living in Buenos Aires, where he had emigrated from Paris after the start of the Spanish Civil War. Working closely with the clients via letters, Bonet designed every aspect of the building, from the overall organization to the materials, interior details, and furniture. The result was a spacious and harmonious house defined by an 8.8m x 8.8m grid of thin metal pillars and vaults, with connected but distinct areas for the different uses. The house was also designed with its natural surroundings in mind, blurring inside and outside, and paying special attention to the nearby pines, dunes, and water.

Coinciding with the exhibition La Ricarda: An Architectural and Cultural Project, organized by MAS Context in Chicago and curated by Iker Gil, the architects Fernando Alvarez and Jordi Roig, preservation architects of La Ricarda, write about this house in an interesting article.

In 1949, Antonio Bonet returns to Barcelona after thirteen years of forced exile in America due to the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939). He receives the job of building a single-family home on a site located next to the La Ricarda lagoon along the Mediterranean seaside in El Prat de Llobregat. Through Joan Prats (1891-1970), instigator of many cultural initiatives during the 1930s, Bonet meets a couple, Inés Bertrand Mata (1915-1992) and Ricardo Gomis Serdañons (1910-1993), who want to build a house that could accommodate family and cultural activities, with a special focus on music.

The Project and its Phases: Space, Time, Technique

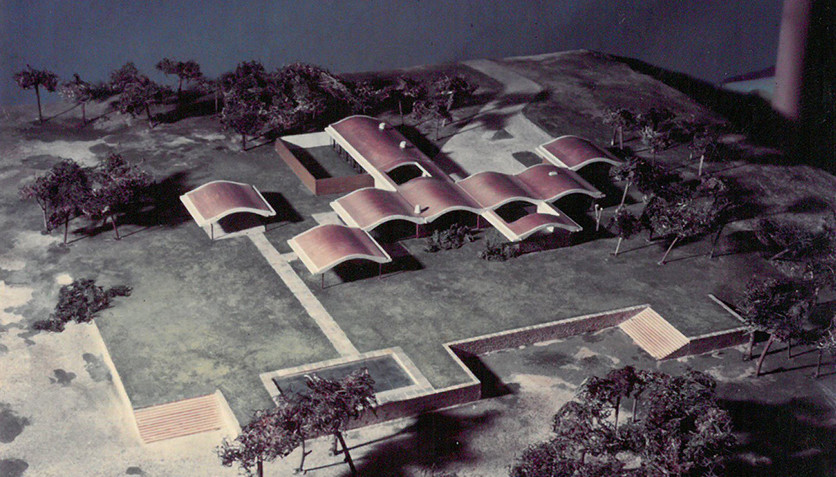

At the beginning of 1950, the Gomis Bertrand family receives the first design for the house which proposed an elevated platform over a grid of pilotis, a large palafitte topped by an expansive “butterfly” roof and considerable terraces connected by ramps, from which you could oversee the landscape. After reviewing this initial idea, the clients asked the architect to reduce the dimensions of the house and to strengthen the connection with the landscape of the site, defined by the presence of a forest of pinus pinea and sand dunes. In May of 1953, Bonet travels to Barcelona and presents a second proposal that shows a radical change in the approach to the surroundings and in the technical-formal aspects of the house. While the first project suggested a floating, strong, and autonomous image, the second project proposed a house that expanded horizontally over a large elevated platform, but also closely connected to the surrounding landscape.

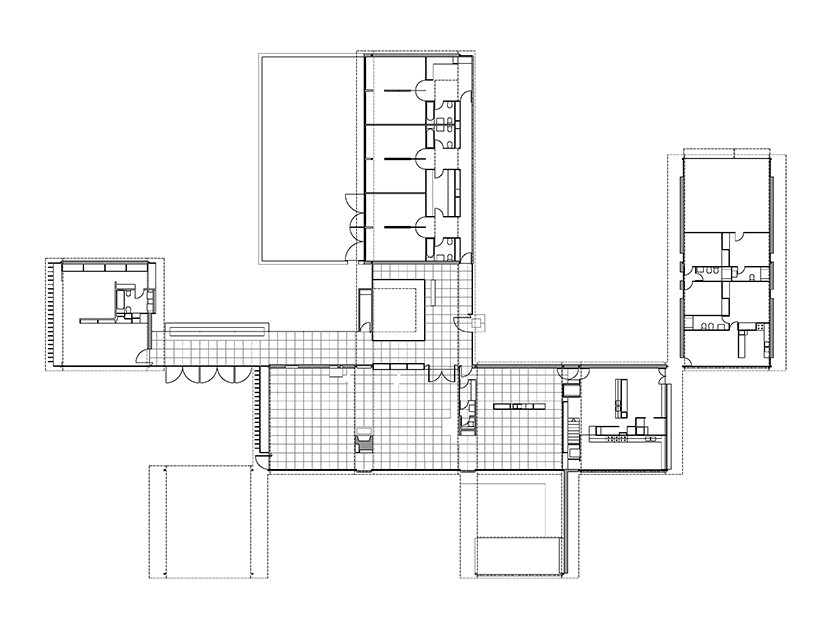

Above this ample platform, elevated about 2.1 meters (6.9 feet) from the natural terrain thanks to slopes and stone banks, Bonet proposed a square grid of 8.82 meters x 8.82 meters (29 feet x 29 feet) that organized both the covered areas as well as the exterior areas of the project. With that decision, the architect was able to not only separate the house from the humidity of the coastal ground and dominate the views but also create an exterior space that is complementary and inseparable from the interior one, subject to the same geometric rules.

During the construction of the house (1957-1963), Bonet continued to revise the technical aspects of the project, introducing small modifications, such as the connection to the independent pavilion, the final location for the pool, and other changes, always conforming to the general modular order. A base plan and a model created by the builder (Emilio Bofill, father of Ricardo and Anna Bofill) were the documents that demonstrate this remarkable work in progress.

The roof of the house has twelve modules defined by a vault made out of concrete and ceramic tiles supported by four slender steel columns that are spread out according to the two main axes. The sequence of living room-dining room-kitchen defines the program facing south while the bedroom wing, the garage, and service area define the axis sea-forest. Finally, the independent pavilion houses the main bedroom.

In La Ricarda, Bonet not only evolved the structural system and interior spaces present in his previous works, he also incorporates the use of the square module to shape the exterior spaces, generating a feeling of harmony. Those modules gain relevance when they are connected to the main living spaces of the house, becoming intermediate spaces, halfway between the interior and the surrounding landscape. The living room has its own vault-porch, the children’s bedrooms open up to a nearly enclosed patio, the dining room has a reciprocal space outside, and the service area also has an associated space. The glass corridor, hardly visible at a distance, provides the covered connection between the independent pavilion and the rest of the house, acting as a windbreaker for the garden in the back. Through these spatial approaches, the house is situated between a rhythmic and almost classical expression of the vaults that determine a rational expression, and a harmonic dialogue with its natural surroundings.

In this almost floating ensemble, the façades, free from any structural role, become glass canvases, ceramic lattices with colorful glasses, weightless wooden brise soleils, and shiny traditional ceramic cladding in bottle-green and ochre-honey colors.

During all these years, the expenses of the restoration of La Ricarda have been paid by the heirs of the Gomis Bertrand. Having addressed the problems that threatened the house twenty-five years ago, there is a need now to focus on the restoration of other elements and on the preservation of the elements that have already been restored. In contrast to the interest of the professionals, students, and fans of modern architecture that continue to visit the house, there is a lack of interest by cultural institutions, public and private, of Spain. To keep and preserve the modern legacy of the twentieth century is as important for future generations as is the preservation of everything that is considered “old.” International examples such as the Robie House in Chicago, Fallingwater in Pennsylvania, Villa Tugendhat in Brno, Sanatorium Zonnestraal in Hilversum, or the library in Viipuri should be the reference. La Ricarda must be saved!

Leave a Reply