Barcelona’s remarkable history of rebirth and transformation. How the city grew, from pre-Christian Romans to Cerdà plan.

Barcelona is in a perfect place for a city. Humans have been settling there, according to archeological remains, as far back as 5,000 BC.

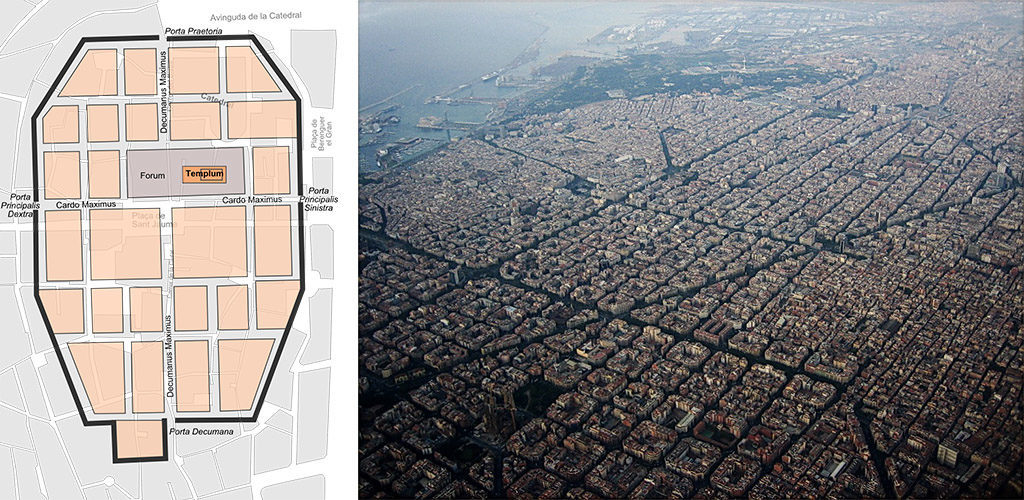

The city’s origins trace back to the Romans, who settled in the area in 15 BC and, in the first century BC, built the medieval city of Barcino. It was small, surrounded by a wall roughly 1.5 kilometers in circumference, with the characteristic Roman grid of perpendicular streets.

In these modest beginnings are already visible two characteristics that would define Barcelona’s development over the years.

First, it began, and has always remained, a bounded and compressed city, dense from its founding. First physical walls and then the limits of geography have hemmed the city in and ensured that its residents are crammed tightly together.

And second, it has always been an intentional city, closely conceived and constructed by central planners. There have been very few periods of unplanned growth in Barcelona history. Unlike so many newer cities, it has not sprawled. Each new burst of growth has been on purpose; there has always been a plan.

Over the centuries, the city has been transformed again and again at the hands of visionaries, mostly notably architect Ildefons Cerdà, still considered one of history’s great urban planners.

How Barcelona’s walls finally fell

After the Roman Empire fell in the fifth century CE, the years saw a series of conquests — Visigoths, Arabs, what have you — but they all reused the existing city.

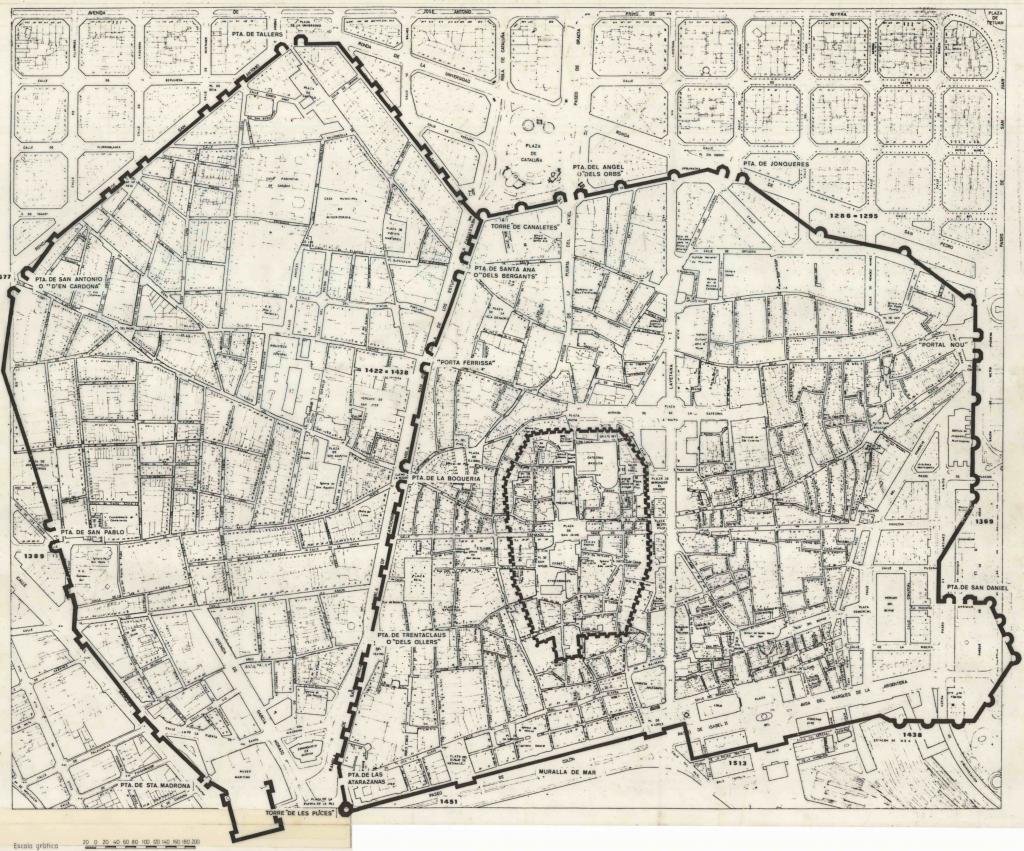

In the Middle Ages, the city grew and became more complex, the center of a region known as Catalonia. An extended wall was built in 1260, and then in the 15th century, the wall was expanded again to encompass the new Raval neighborhood. The part of the plain outside the wall was used for agriculture to provision the city.

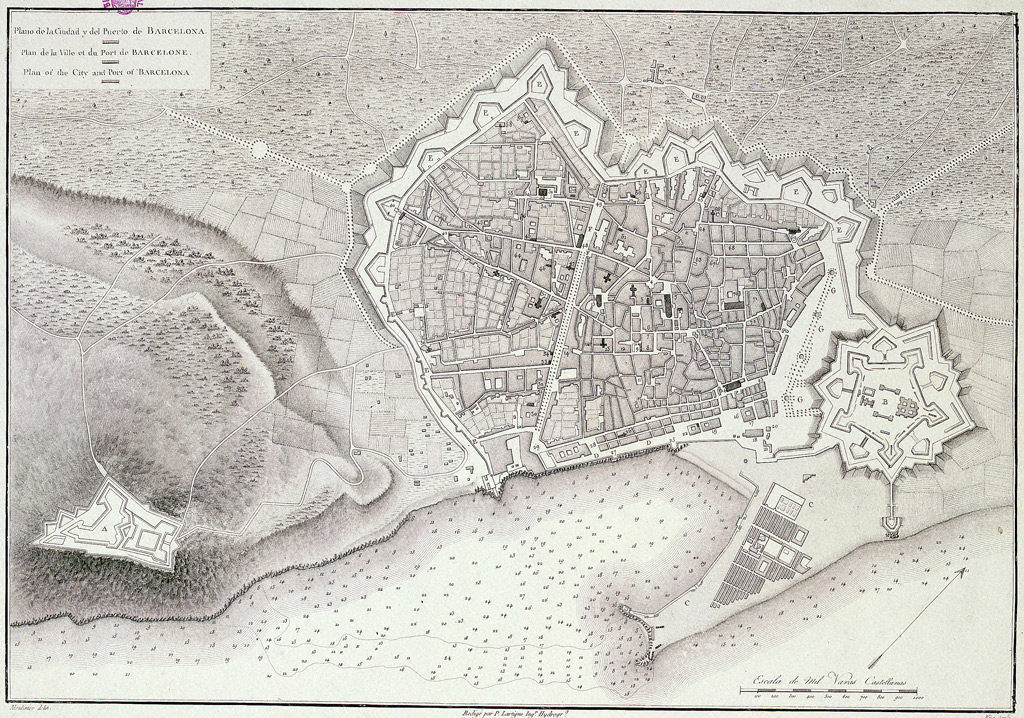

In 1714, the War of the Spanish Succession ended and Barcelona was on the losing side. Upon its surrender, in order to suppress any future challenge, Philip V abolished many of the city’s institutions and charters, built a fortress citadel to keep an eye on it, and forbid Barcelona to grow beyond its medieval walls.

Remarkably, the wall around the city stayed in place — hemming in a growing population and almost completely separating the city from the sea next to it — for two more centuries. By the middle of the 19th century, population density was the highest in Spain, working conditions were miserable, sewage was out of control, water was dirty, and the city was struck by a series of cholera epidemics and riots.

By 1854, when the Spanish government finally gave permission to take the wall down, it was one of the most hated structures in Europe. Townspeople immediately went at it with crowbars and pickaxes; it took 12 years to completely remove it.

Then came one of the most extraordinary and underappreciated chapters in urban design history — a chapter that, though 175 years in the past, contains many omens and warnings for Barcelona’s current efforts.

Cerdà’s utopian plan for Barcelona

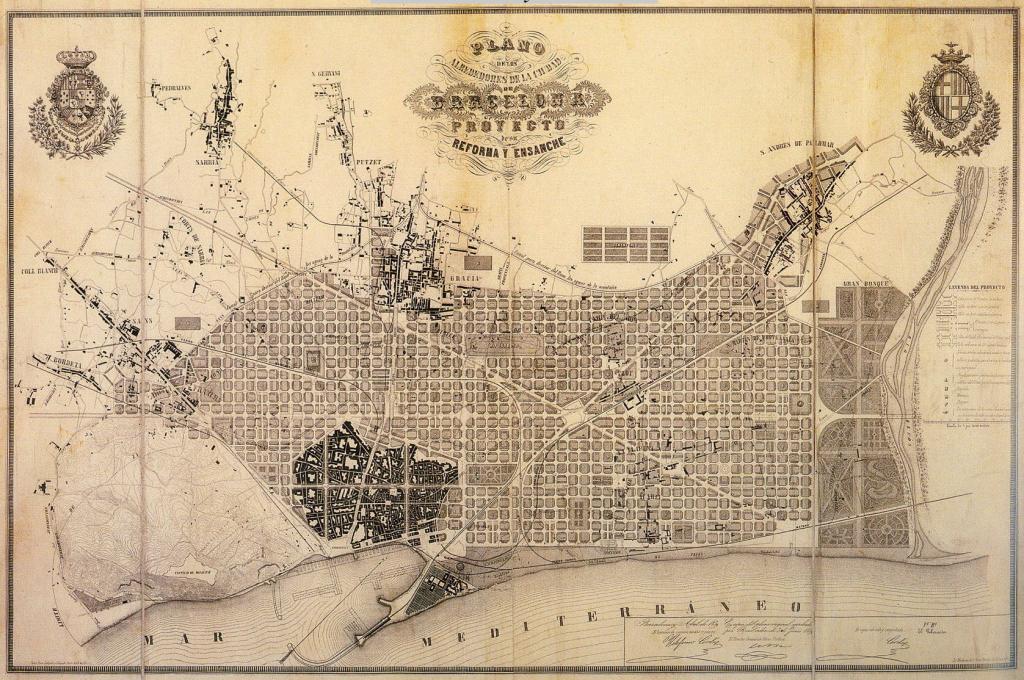

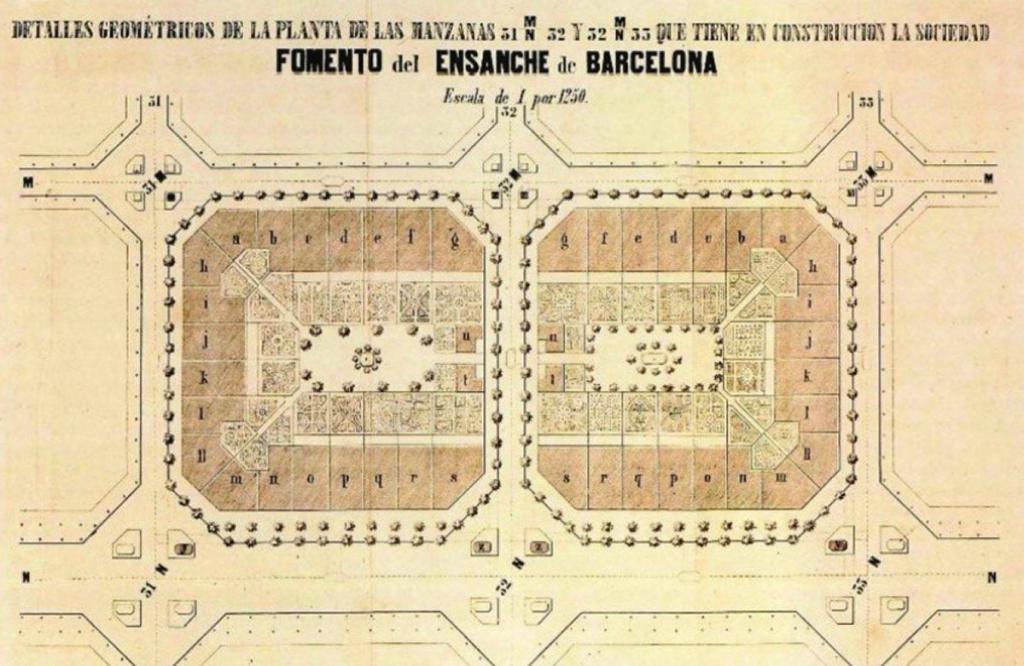

As soon as the wall’s demolition was announced, plans began for an expansion of the city. In 1855, the central Spanish government approved a plan by architect Ildefons Cerdà.

Cerdà was horrified by the conditions of the working class in Barcelona and set out to make his extension of the city — the Ensanche in Spanish, or in Catalan, as the district is still known today, the Eixample — a model of orderly, clean, safe, hygienic urban living.

Two things are worth noting about Cerdà’s plan.

First, he took what was, for the time, an exceptionally holistic view of urban quality. He wanted to ensure that each citizen had, on a per capita basis, enough water, clean air, sunlight, ventilation, and space. His blocks were oriented northwest to southeast to maximize daily sun exposure.

And second, his plan embodied what is — then and today — a striking egalitarianism. Each block (manzana) was to be of almost identical proportions, with buildings of regular height and spacing and a preponderance of green space. Commerce was to take place on the ground floor, the bourgeoisie were to live on the floor above (rather than in mansions at the edge of town), and the workers were slated for the upper floors. In this way, they would all share the same streets and public spaces, exposed to the same hygienic conditions, reducing social distance and inequality.

Each 20-square-block district was meant to be largely self-contained, with its own shops and civic facilities. Hospitals, parks, and plazas were to be spaced evenly throughout the city, to maximize equality of access.

In 1859, in response to criticisms, Cerdà released a modified version of the plan, with narrower streets no more than 20 to 30 meters wides and somewhat deeper buildings, with more room for commerce. The plan was approved by royal decree in 1860.

Though Cerdà’s manzanas were (and are) criticized for their uniformity — the sameness is said to leave no room for great monuments or idiosyncratic artistry — it is just that underlying uniformity that has proven so endlessly adaptable.

The repeating structure of the blocks means that as social and economic circumstances change, old buildings can be shifted in use or ripped out, or multiple buildings combined.

Originally, each of Cerdà’s blocks was to have buildings on just two sides (sometimes three), occupying less than 50 percent of the total area, with the bulk of the interior space devoted to gardens and green space. The buildings were to be low enough (no more than 20 meters tall and 15 to 20 meters deep) to allow for almost continuous sunlight in the interiors during the day.

The goal was to combine the advantages of rural living (green space, fresh air and food, community) with the advantages of urban living (commerce, culture, free flow of goods and ideas).

Though in many ways, Cerdà’s plan won in the end — its legacy is still clearly visible in Barcelona’s Eixample — it was compromised by commercial and political considerations from the outset.

Leave a Reply