Lucien Kroll, approach to an unconventional vision of architecture.

Anyone interested in a history of participation in architecture, sooner rather than later, is obliged to talk about the work of a Belgian architect whose work is growing every day: Lucien Kroll.

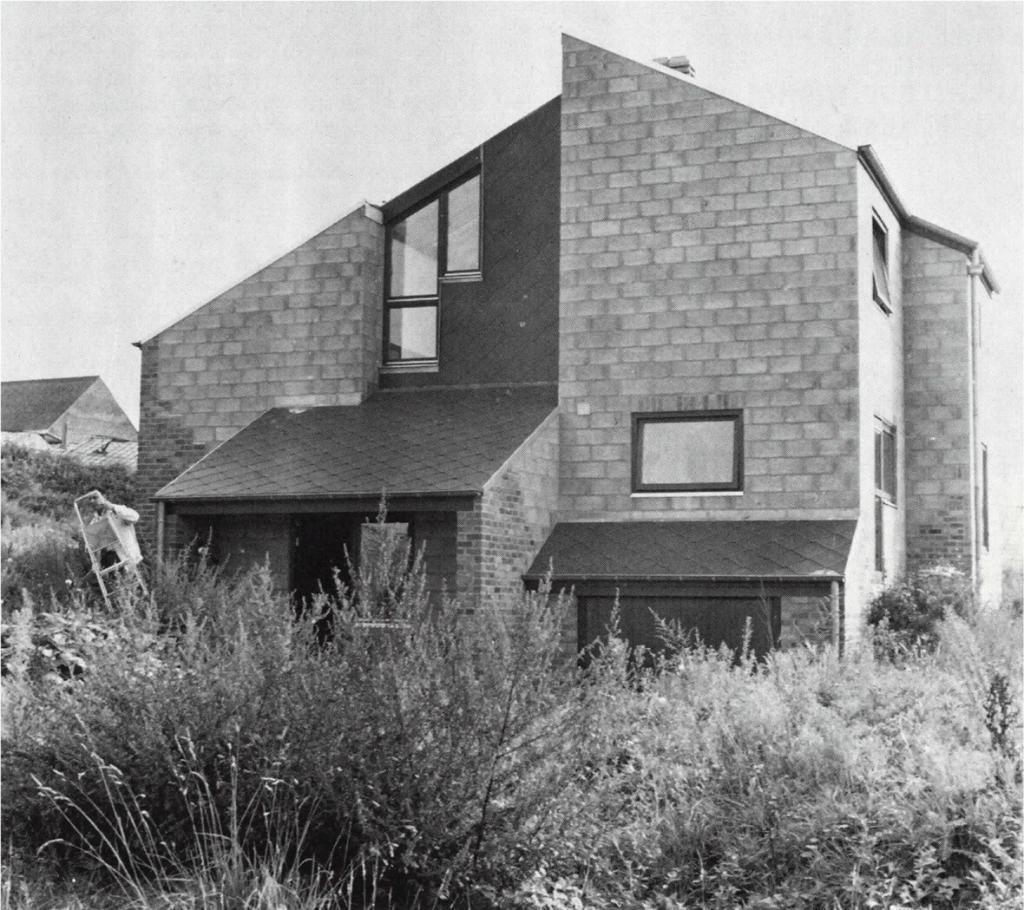

C’est l’exception qui est la regle generale’. This brief remark of the architect Lucien Kroll sums up his architectural approach. His most famous buildings, the living quarters of the medical students and the University of Louvain at Woluwe, now look like fragments of an old city. The visual aspect of his work initially looks totally anarchic but beneath it is a serious attempt to create buildings that do not impose on their users.

To put it mildly, Lucien Kroll’s approach to architecture is unconventional. There are no past masters to whom he turns for inspiration; his buildings derive solely from rigorous application of his own philosophy of what a building should be.

Kroll’s descriptions of the conventional products derived from the Modern Movement are laced with the adjectives of oppression: the administrators who commission designers are fond of ‘paramilitary models’; Pruitt-Igoe in St Louis (and developments like it) are the products of generations of ‘somewhat militaristic architects’; the dark glazed windows on the wall of a contemporary office presents a ‘fascist facade’. ‘The programme called for separate rooms. We made them completely regular, like ruled metric paper, and in the facade we used reflecting glass like the sunglasses of American policemen.’

Kroll builds cheaply, using man’s most basic building materials.

He has a fondness for artificial slate roofing tiles-mostly the kind made by Eternit: ‘They are cheap, very tough, they accept moss, and live with the weather’. His favourite images are of lichens and lush, succulent plant growth, of weathered rock and the haphazard placing of stones to form walls made by unskilled workers. He likes things built by man that look as if they have been there forever, absorbed into the landscape. Indeed, landscaping, designed by his wife Simone, is an integral part of any design. Scarcely a hard surface is envisaged without its future covering of ivies or virginia creeper. Kroll is striving to bring his buildings as close as possible to nature, to provide as ‘natural’ a place for fallible, unpredictable man.

This explains why he sees no contradiction in building new, hard up against the old, of using concrete blocks to repair an old weathered brick wall, of using sheets of glazed skylight in the roof of an ancient timber barn. Homogeneity of form, and materials, is artificial he says. Large surfaces of brick, like the construction of formal spaces in architecture constitute the victimisation of the inhabitant by the architect. So not one of his walls will be built entirely of the same material concrete blocks and brick, of different sizes and colours, pave and slates are interspersed -frequently at the discretion of the bricklayer. Stones from the earth run up the wall; roof tiles run down to meet them. It is Kroll’s way of building organically, of trying to create buildings that do not impose themselves on their occupants, that relate to people.

Kroll is at pains to gather the commitment of both the future occupants of his buildings and the workers on his sites and involve them all in the design and construction of the new building. He is anxious that people should get the frame for living that most suits their way of life. He wants to preserve the traditions of craftsmanship and deplores trends towards heavy prefabrication and increasing specialisation.

For all his care for those who will use his buildings, Lucien Kroll is not popular in Belgium. His views are understandably at variance with those of the establishment. At first sight, his best known work, the new buildings for the University of Louvain at Woluwe on the outskirts of Brussels are a complete jumble, their facades a totally disordered (one might say anarchic) collection of brick, glass, grills, balconies, grey tiles, staircases. The authorities dislike them so much that in 1977 they dismissed Kroll as architect.

They have threatened to tear them down, and have already destroyed the planting which was beginning to climb up the buildings. But Kroll’s design is ingenious. Inside the residences, rooms on a variety of levels have been designed to be shared by students in small self-contained units, centred around a staircase. The bedrooms have all been designed to give direct access to a private balcony or terrace outside; internally walls can be built or taken down to give more or less rooms. They are flexible, adaptable, the sun comes in in the right places, and they are great fun to be in.

Many of the principles that governed this design are repeated in more projects.

There is an inherent contradiction in Kroll’s approach to architecture. For the buildings he has designed all bear the unmistakable stamp, the trademarks of Lucien Kroll, architect. By virtue of his belief in what architecture should be and his skill as a designer, he cannot but impose his view on society or manipulate those who use his buildings. The involvement of his users and builders notwithstanding, are the buildings he produces anymore the product of spontaneous, organic growth than Buckingham Palace? It is a dilemma that he is aware of.

But that Kroll can indeed bring about a successful ecological marriage between new and old building and natural vegetation can be seen in his project for the Dominican Fathers at Froidment; that he has won the hearts of his users is apparent in the remark of the Dominican sister at the convent at Ottignies, who, despite reservations about the materials and details of the building, said: ‘When we moved in, we felt at home immediately. He did exactly what we wanted in his completely original way.’

“A complex, diverse architecture that shows its contradictions and regrets will stimulate random creativity both during its conception and throughout its use. It will be an architecture-weaving, without rigid limits between this and its context, between today, yesterday and tomorrow, between its authors and its users. Only then will it be pedagogical. Besides, his disappearance, his relinquishment of authority is in no way contrary to a personal art!”

Leave a Reply