Cerdà’s was the first meticulous scientific study both of what a modern city was, and what it could aspire to be.

Constricted by its medieval walls, Barcelona was suffocating – until unknown engineer Ildefons Cerdà came up with a radical expansion plan. Rival architects disparaged him, yet his scientific approach changed how we think about cities.

In the mid-1850s, Barcelona was on the brink of collapse. An industrial city with a busy port, it had grown increasingly dense throughout the industrial revolution, mostly spearheaded by the huge development of the textile sector.

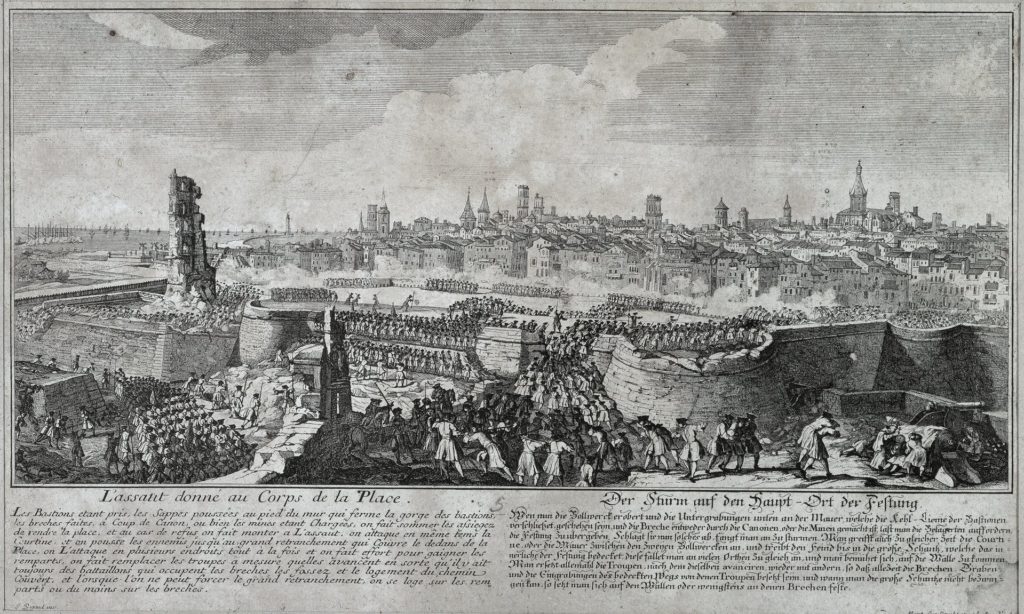

The city was living at a faster pace than the rest of Spain, and was ready to become a European capital. Yet its population of 187,000 still lived in a tiny area, confined by its medieval walls.

With a density of 856 inhabitants per hectare (Paris had fewer than 400 at the time), the rising mortality rates were higher than those in Paris and London; life expectancy had dropped to 36 years for the rich and just 23 years for the working classes. The walls were becoming a health risk, almost literally suffocating the people of Barcelona – who were addressed directly in the following public statement of 1843:

“‘Down with the walls!’ has said this province’s council, and ‘Down with the walls!’ has no doubt answered your town hall, which knows the importance of making this girdle disappear that is squeezing and choking us.”

Demolition work would finally start a year later. Now the city and the Spanish government had to design and manage the sudden redistribution of an overflowing population. It was a controversial and highly political decision – which ultimately led to the then unknown Catalan engineer Ildefons Cerdà’s radical expansion plan for a large, grid-like district outside the old walls, called Eixample (literally, “expansion”). In the process, Cerdà also invented the word, and study of, “urbanisation”.

By the early 19th century, the old walled city of Barcelona had become so crammed that the working classes, bourgeois society and factories all co-existed in the same space. “Everyone was suffering the consequences of an Asian-level density,” says the writer and essayist Lluís Permanyer, whose book Eixample: 150 Years of History chronicles that period.

As there was no more land left inside the city walls, all kinds of inventions were used to build more lodgings – houses were literally being created on empty space. Arches were erected in the middle of streets to be built upon, and a technique called retreating façades saw house fronts extended out into the street as they rose up – until they almost touched the building opposite (this practice was banned in 1770, as it prevented air circulation).

Traffic – in those days, horse-drawn carts – was problematic too: the city’s narrowest street (now gone) was just 1.10 metres wide, while around 200 were less than three metres across. This, combined with residents’ Mediterranean way of life (which meant being on the street whenever it was light – and in the case of some artisanal professionals, working there too), worsened an already severe lack of hygiene in the city.

By the early 19th century, the old walled city of Barcelona had become so crammed that the working classes, bourgeois society and factories all co-existed in the same space. “Everyone was suffering the consequences of an Asian-level density,” says the writer and essayist Lluís Permanyer, whose book Eixample: 150 Years of History chronicles that period.

As there was no more land left inside the city walls, all kinds of inventions were used to build more lodgings – houses were literally being created on empty space. Arches were erected in the middle of streets to be built upon, and a technique called retreating façades saw house fronts extended out into the street as they rose up – until they almost touched the building opposite (this practice was banned in 1770, as it prevented air circulation).

Traffic – in those days, horse-drawn carts – was problematic too: the city’s narrowest street (now gone) was just 1.10 metres wide, while around 200 were less than three metres across. This, combined with residents’ Mediterranean way of life (which meant being on the street whenever it was light – and in the case of some artisanal professionals, working there too), worsened an already severe lack of hygiene in the city.

Barcelona’s epidemics were devastating: each time they broke out, 3% of the population died, according to Montserrat Pallarès-Barberà, geography and urbanism professor at Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. Cholera alone killed more than 13,000 people between 1834 and 1865.

Into this came Cerdà. His plan consisted of a grid of streets that would unite the old city with seven peripheral villages (which later became integral Barcelona neighbourhoods such as Gràcia and Sarrià). The united area was almost four times the size of the old city (which was around 2 sq km) and would come to be known as Eixample.

This unknown engineer was revolutionary in what he envisioned – but also in how he got there. Cerdà decided to avoid repeating past errors by undertaking a comprehensive study of how the working classes lived in the old city. “He had thought he would find all these urbanism books, but there were none,” Permanyer says. So he was forced to do it himself.

Cerdà’s eye was as careful as it is fascinating. His was the first meticulous scientific study both of what a modern city was, and what it could aspire to be – not only as an efficient cohabiting space, but as a source of wellbeing (not a straightforward concept back then).

Leave a Reply